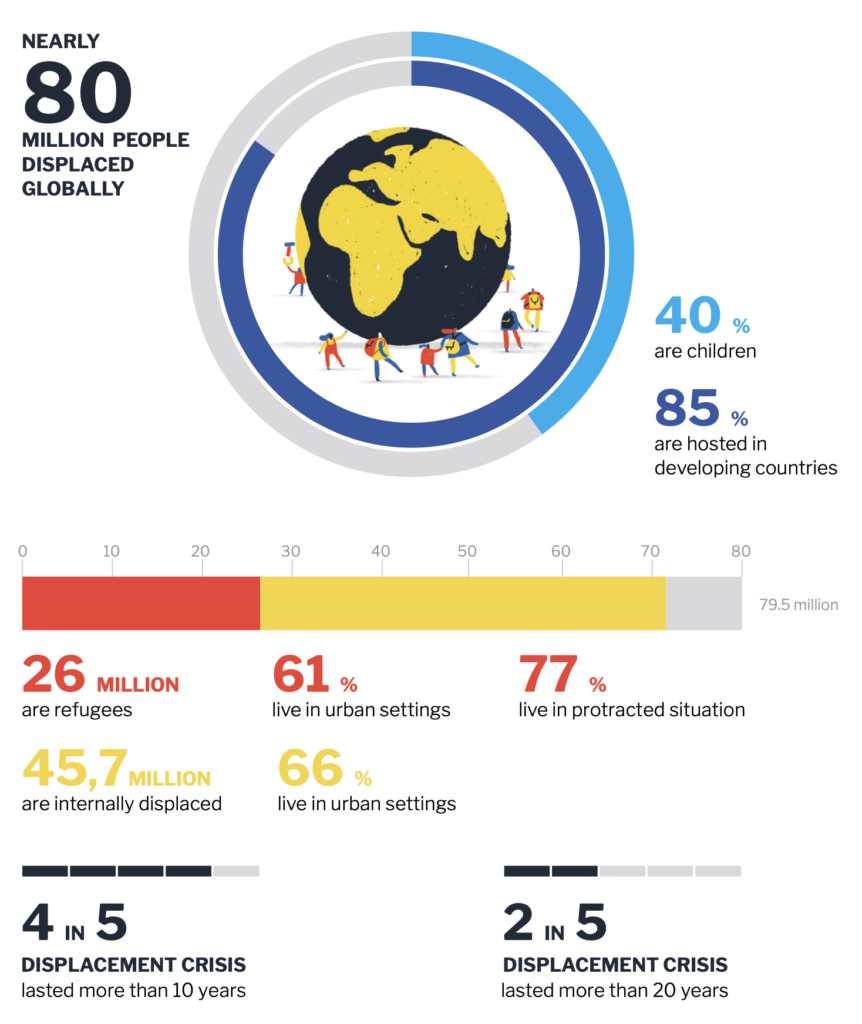

Nearly 80 million people were displaced globally by the end of 2019. Their number has doubled in less than a decade and is at a record high. 85 per cent of displaced people are hosted in developing countries. Of these, 26 million are refugees and 77 per cent have been in protracted situations lasting more than five years (UNHCR, 2019). The average length of such protracted situations is increasing. From 1978-2014, over 80% of all crises lasted more than ten years, and 40% lasted 20 or more years (Crawford et al., 2015).

Displaced people are increasingly living in urban areas. The proportion of the refugee population based in urban settings was estimated at 61 per cent in 2018 (UNHCR, 2019) and two thirds of internally displaced people resided in cities in 2019 (UNHCR, 2020). In urban areas, displaced people often end up living in peripheral informal settlements with the urban poor, who are also socially and economically marginalised. Developing countries that host displaced populations often face challenges in providing the basics for their own citizens, which can increase social tensions when refugees arrive. Forty per cent of the world’s displaced people are children. In the Syrian refugee crisis, nearly 45 per cent of registered Syrian refugees in Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt were under the age of 14 (UNHCR, 2017).

When children and their families leave their homes behind, they do so in search of safety. However, displacement exposes children and their families to a wide range of additional distress and dangerous events. The consequences of displacement on children’s health, education, and security can be severe. The housing conditions in which the displaced settle, commonly characterised by minimum hygienic practices and unsanitary conditions, are harmful to children’s health as they increase the risk of infectious diseases. The loss of income that often accompanies displacement can force families to send their children to work rather than school. Poverty is a major burden for children and their families, leading to high levels of stress, and forcing children into child labour and early marriage.

Diagram 4

Displacement key data

Source UNHCR 2020 Global trends: Forced displacement in 2019

Common challenges faced by displaced children:

- Food insecurity

- Exposure to violence

- Lack of safety

- Poverty

- School dropout

- Child labour

- Exposure to hazards

- Mental health issues

- Separation from family and friends

- Discrimination

- Barriers to access healthcare

- Lack of play opportunities

- Poor housing conditions

- Overcrowded and inadequate infrastructure and services

Displaced children may also experience the breakup of their families and communities, and are burdened with challenges, including changes in family dynamics. Children can take on the role of providers for the family, or become caregivers for their younger siblings or parents who have

been physically or psychologically affected by their experiences. Children may experience highly distressing events before, during and after forced displacement, and these may have long-lasting effects. Such events may result in physical disability and deterioration of physical health, cultural and social losses, and psychological suffering such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety.

Children’s individual responses to traumatic events differ based on factors including gender, age, personality, cultural background, personal and family history. The nature of the traumatic events they are exposed to, and the frequency and length of their exposure, are also significant factors. Children’s exposure to violence, the degree of their exposure to threat, the accumulation of adverse experiences, and the duration of their exposure all increase the possibility of children acquiring mental health problems.

Forcibly displaced children are often exposed to additional risks, including living with caregivers who are also experiencing trauma or stress, having irregular status in the host country, being discriminated against, living in poverty, separation from their family and community, and multiple traumas. The proximity of supportive caregivers (which include parents) to children during terrifying events can significantly mitigate the effects of these experiences on children. This is also why engaging parents and caregivers in co-design processes is recommended and can provide lasting benefits for displaced children’s wellbeing (El-Khani, Ulph, Peters & Calam, 2016).

Children from both host and refugee communities may experience issues with safety in their environments. The influx of refugees into their areas may limit the ability of children from host communities to play in playgrounds or courtyards, as these spaces may become overcrowded or turned into spaces for refugees to live in. Both refugee and host community children may face barriers to school attendance. Increases in traffic and costs of transportation, and decreases in income, may affect school attendance of host community children. Moreover, food consumption, access to healthcare and health problems, access to play spaces and time to play may be negatively affected for both refugee and host communities. Since most refugees resettle in low and middle-income countries, poverty is usually a factor affecting not only refugees but also host communities.

Some of the most widely reported factors that may protect displaced children and help them overcome highly distressing experiences include good quality schools, childcare facilities, and safe spaces for play and learning. Restoring routine, play, and order in displaced children’s lives, as well as support from families and communities, may help children recover from difficult experiences. One of the main ways of reintroducing routine into children’s lives is to resume their schooling. However, in Lebanon, over half of Syrian children were not attending school in 2018 (UNHCR, UNICEF, and WFP 2018).

Children are agents and rights holders, powerful co-creators of knowledge, and experts on their own lives. Children’s participation provides researchers and practitioners with a unique understanding of children’s life experiences. This is even true for the youngest children, whose voices can be heard when appropriate methods are used.

A more detailed discussion on children affected by displacement and how to work with them can be found in the DeCID Thematic Briefs: