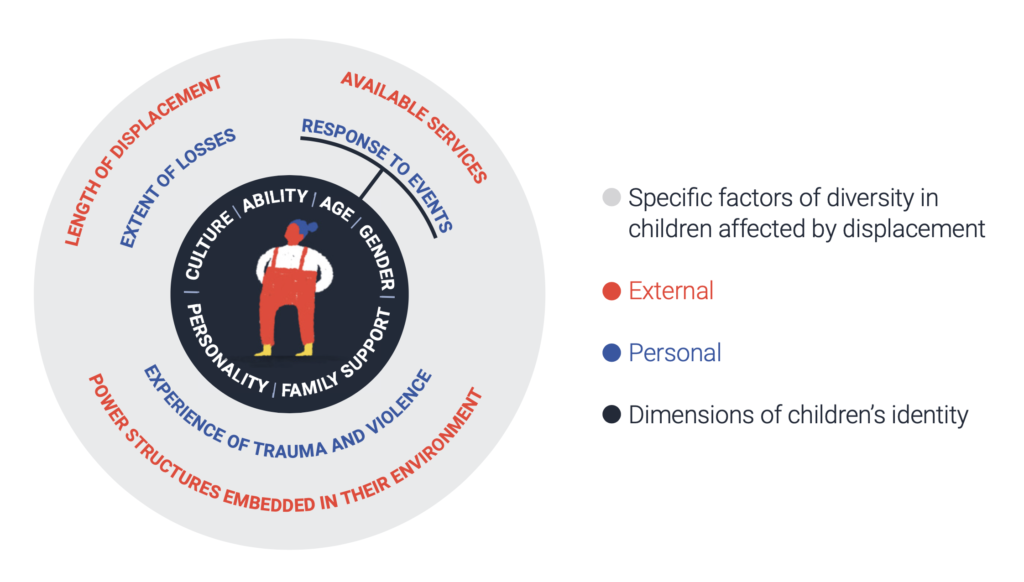

Children make up around half of the refugee population worldwide, and 40% of the 80 million displaced people globally, with the majority settling in urban areas (UNHCR, 2020). Children’s experiences of displacement are very diverse and influenced by a number of external contextual factors, such as the length of displacement, availability and quality of services, and power structures embedded in their environments. A number of personal factors are also important, such as trauma and/or violence experienced by them or family members, and the extent of the losses experienced. Individuals’ diverse responses to these situations are influenced by their gender, age, ability, personality, family structure, culture, and religion.

Therefore, responses must be tailored to the realities of children affected by displacement in a particular context.

Diagram 1

Displacement key data

Children affected by displacement are a very diverse group. Diagram 1 presents some dimensions of their identities and diversity factors. These dimensions interact in complex ways, requiring approaches that uniquely value the diversity of each child, and responses suitable for the group.

The quality of spaces available to children has an important impact on their development and wellbeing. As displaced families often settle in the poorest parts of cities and live in overcrowded, poor-quality housing alongside the most vulnerable residents, their children often suffer from poor access to quality public, learning and play spaces.

The handbook will discuss how co-designing built interventions with children affected by displacement can:

- empower children and have a lasting positive impact;

- improve social cohesion, inclusion, social capital, and integration between refugees and host communities, and within the refugee community;

- have a positive impact on the local economy, build capacity and provide employment; and

- deliver better social infrastructures (child responsive urban public spaces, schools, playgrounds) for children and their communities.

Despite their impact, there is an undersupply of built interventions that have been co-designed with children. This is because: they require professionals from different specialisms to work together, and often organisational structures do not make these collaborations easy; their additional value is

difficult to recognise; and they require a larger initial investment compared to the built product alone. Furthermore, these interventions often present multiple operational challenges linked to safeguarding, cultural norms and appropriateness. This prevents many organisations from taking on such projects, despite the strong need for children’s voices to be part of design responses in displacement contexts.

The DeCID handbook was born out of a lack of practical guidelines for codesigning built interventions with children affected by urban displacement. It was created by a mixed team of practitioners and academics from different disciplines, and via a research process involving interviews and thematic discussions with varied related practitioners.

While the team made efforts to make this handbook applicable to a wide variety of contexts, and to include examples from different regions, a significant proportion of the input was provided by people working in areas of Lebanon affected by mass displacement from Syria. As we believe in the importance of adapting interventions to their particular context, the reader should take this into consideration and assess what may, or may not, be relevant in their case.